Residents of Reston can correctly surmise that James Rossant (1928-2009), its master planner and one of its primary designers, was well grounded. This is the architect who, with partner William Conklin, planned one of the most visionary new cities of its time in the United States, integrating housing, commerce, recreation, culture, and landscape into a complex and complete ecosystem that fostered and sustained a sense of community. Here a human being could live through all life’s stages, cradle to grave, in harmony with nature and society. He also designed many of its initial buildings, open spaces, and even sculptures.

A single drawing of a low-rise complex of handsome Modernist apartments surrounding a landscaped entry court—the view invites the eye and body into its architectural embrace—summarizes his vision. It’s a moment in a much larger urban fabric that, like a Rosetta stone, unlocks and explains the intentions designed into thousands of Reston acres. The drawing itself is disciplined and, like the project itself, embodies humanistic city-planning ideals of the 1960s, originating in the progressive Garden City movement of the 19th century. The rationality, grace, comfort, and humanity embodied in the design of this Modernist apartment complex forms a cornerstone for what is today a viable community nearing 65,000 people.

Rossant had a serious mind, a disciplined training, and a gifted hand. The drawing introduces the exhibit, and with the rest of his drawings constitutes an autobiography of an imagination fueled by a sense of humor—and the absurd—that informed and drove the hand and mind of Reston’s creator.

Rossant trained at Harvard under Walter Gropius at a time when architecture had an almost religious devotion to the right angle. In fact, Rossant is best known for a series of drawings, published as Cities in the Sky, that respect the grid, almost to delirium. In magisterial drawings, Rossant drew groundless cities floating in air, with urban matrices layered in gridded tartans of linear buildings, crossing each other in neighorhoods extending toward infinity. His imagination drove rationality to excess. The visions capture the adventure of real space stations of that time and megacities invented by Japanese and French colleagues.

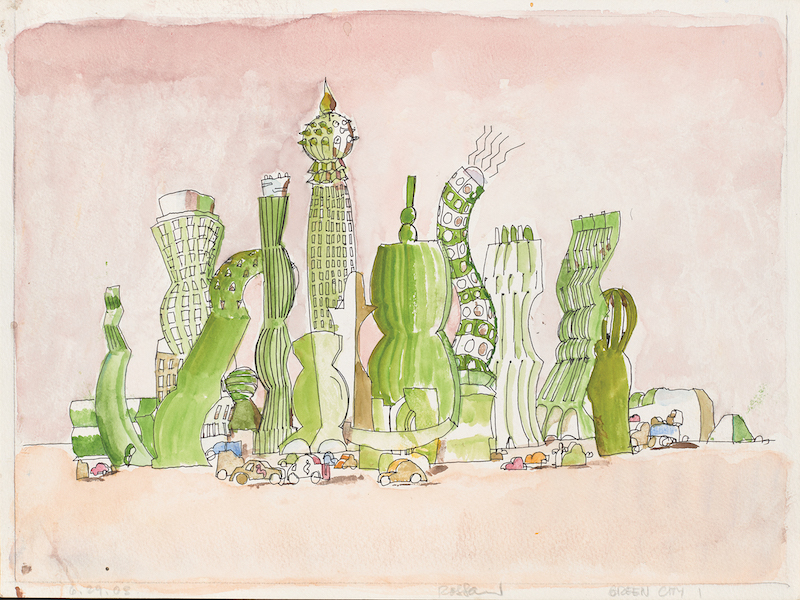

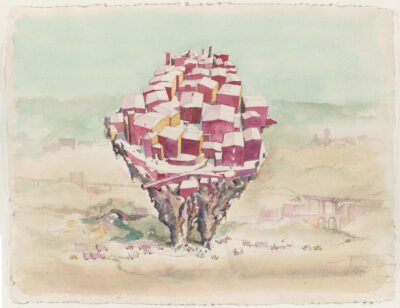

This exhibit Cities and Memory focuses on the intimate side of his vision rather than the heroic. Other than the single view of that apartment complex, the drawings fly off the grid, off the wagon of rationality, into a surrealism and humor of imagination liberated from the right angle and architectural propriety. These drawings peel back the conscious control of a Gropius student to peer into the subconscious, revealing perhaps the child within. These are temperamentally joyous drawings, propelled by curiosity and a spirit of exploration. Some are delightfully preposterous, like Green City 1, which looks like a skyscraper forest of vertical vegetables growing in a garden city. Another drawing imagines a village, brimming full, perched atop a teetering cliff (Untitled [undated] – Where to Stand).

Compared to the panoramas of Cities in the Sky, these are graphic bagatelles but even as bagatelles they contain theses. First is the necessity of delight that Rossant scripts into the environment. Beyond the deliberate, well-drawn amusement, however, is his fundamental interest in the city, constituted by buildings that form part and parcel of a whole, not simply stand-alone objects. Rossant’s cities are always integrated into ecosystems consistent within their founding principles, even if they are cartoons. In one drawing, he plays on an architectural pun, moldings that are called “profiles,” and he invents a city populated by “profiles,” each building as individual as an individual (Sullivan Street). Buildings have the singularity of people, each with an identity. The city is personal.

After retirement, Rossant the urbanist lived in the country, first among the fields and orchards of Upstate New York and then Normandy, France. His subject matter changed. In New York, he had looked out the window of his home in SoHo or out his office window and saw Manhattan. In the country, he saw fields. It was a different sort of beauty requiring a different brush.

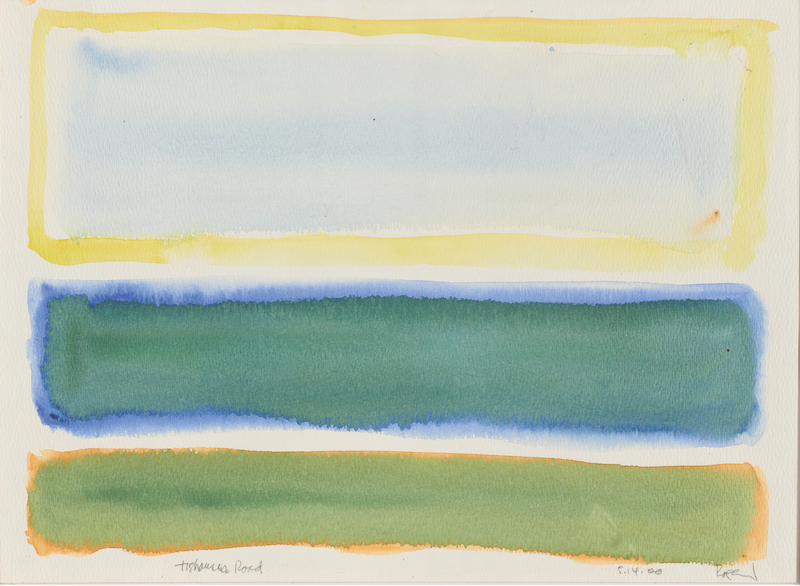

He returned to the watercolors of his youth and invented landscapes tethered to the reality of cows (Claverack), while arcing toward the abstraction of Rothko (Tishauser Road). He specialized in blooms of paint that grew on paper into green fields, spotted with trees (Painting with Paint Tubes). He stacks fields, forests, mountains, and skies atop each other in layers implying a depth of field into landscapes that recede into distance (Claverack – West to Catskills). Some are pure abstractions, a layer of color bleeding into another layer of color, fused. One sublime landscape focuses on a single red truck, rumbling through the serene beauty of a bucolic landscape, as if in a cartoon (The Red Truck). The imagination that could build a whole city accommodating tens of thousands of people embraced a lonely red truck with endearing humanity.

Rossant’s graphic imagination was migratory. His drawings and paintings poked into corners of the mind that strict architectural discipline often misses and dismisses.

His architecture was predicated on a mind, hand, and eye that escaped the rules.

Joseph Giovannini heads Giovannini Associates, a design firm based in New York and Los Angeles. He holds a Masters in Architecture from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Mr. Giovannini has written on architecture and design for four decades for such publications as the New York Times, Architectural Record, Art in America, Art Forum, and Architecture Magazine. He has also served as the architecture critic for New York Magazine and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. His latest book is Architecture Unbound: A Century of the Disruptive Avant-Garde (Rizzoli). He is now working on a biography of Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid.

1 Comment

Add Yours[…] Architect and critic Joseph Giovannini writes on James Rossant’s vision and legacy. Read his full review here. […]