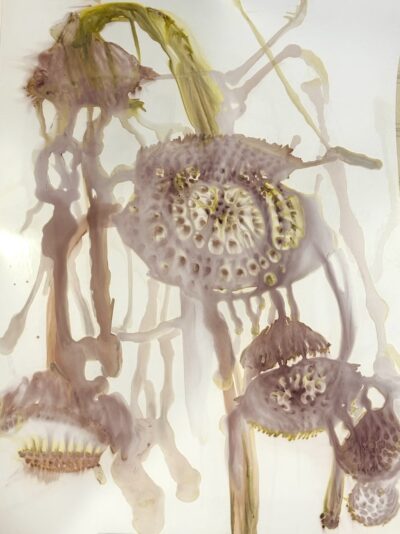

Mary Sebold curated the poetry for the “Night and the Desert Know Me” exhibit at the Smith Center for Healing and the Arts as part of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here DC 2016 project. This interview with Mary by Fenwick Gallery Graduate Assistant Sarah Irvin is accompanied by a poem by Al-Mutanabbi along with artwork by Phyllis Plattner currently featured in the Smith Center exhibition on view through March 5th.

Sarah Irvin: What is your background and how did this influence your decision to become involved with the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here DC 2016 project?

Mary Sebold: I have a degree in Arabic literature and Middle East Studies from the University of Pennsylvania and lived and studied in Syria in the 1980s. For many years, I directed cultural and language programs at the Middle East Institute here in Washington, DC. After studying public health and working locally and in the Middle East, I got interested in arts in health. That’s why I visited the Smith Center last year. They saw my background and asked me to help them by curating the poetry for the Night and the Desert Know Me exhibit. I suggested concentrating on Iraqi poetry and art because of the country’s rich literary and visual arts output, past and contemporary. I enjoyed selecting the poems and working with Shanti Norris, the director of the Center, and Spencer Dormitzer, the head of the Center’s gallery.

SI: What was the curatorial approach to the exhibit at the Smith Center and how did it respond to and reinterpret the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here DC 2016 project?

MS: As far as the poetry goes, I wanted—without labeling anyone—to represent the incredible diversity of Iraq. Throughout history, it’s been a land of many ethnicities, languages, and religions. So I selected seventeen poems—from Gilgamesh, which was originally recited and recorded in ancient Sumerian and Akkadian, to present-day works in Arabic and Kurdish. Some of the poems were written by Christians; others, by Muslims. There’s even a piece by a well-known Mandaean Iraqi poet.

Ten of the seventeen poems inspired the twelve Iraqi and Western artists in the show. Two poems were used twice. One of the Kurdish poems found voice in two paintings by the same artist. One of the four Western artists found inspiration in the poem by Al-Mutanabbi (915–965 CE). The title of the exhibit comes from one of the couplets in his poem.

SI: How has the interdisciplinary nature of the project found a voice through the Smith Center Exhibit?

MS: The exhibit combines two broad artistic disciplines (literature and visual arts) and two fields (arts and health). I think it was healing for the artists, the local Iraqi community, and perhaps others, who have suffered greatly from conflict in recent years. It offered an opportunity for the Iraqis to celebrate their arts and culture. It also allowed non-Arab, non-Iraqi residents of the DMV a chance to learn about a country they (and Americans in general) know little about. You can’t make war that easily against people you meet personally. You can’t destroy a culture you come to appreciate.

Abu al-Tayyib Ahmad ibn al-Husayn

al-Mutanabbi (915–965)

Excerpted from a qasida (poem) translated from Arabic by Arthur Wormhoudt

My laughter tricks the stupid fools

until I hit them with tooth and nail.

When you see the lion bare his teeth

don’t think he merely means to smile.

Bloody malice has aimed at my heart

but I shot from horseback inviolable.

Hind and front legs were one motion

no need for hand or foot to spur him.

With polished sword amidst the armies

I struck while death’s wave churned;

a horse, night and the desert know me

sword and spear and paper and a pen

In Poems from the Diwan of Abu Tayyib Ahmad ibn Husain al Mutanabbi. (Oxford: Shakespeare Head Press, 1968).

The untitled qasida (of thirty-six couplets) comes from the part Al-Mutanabbi’s diwan (oeuvre) relating to Sayf Al-Dawla, who ruled from Aleppo, Syria (945–967). al-Mutanabbi wrote the qasida in response to other poets who had slandered him. The last couplet lends its name to the Smith Center exhibit and is among the most famous in Arabic literature.