In March, I had a great conversation with artist Sarah McDermott about her book Channel & Flow, which was included in our Artists’ Maps exhibit. The book is about McDermott’s experience following the struggling Tripps Run stream in Northern Virginia. Although McDermott is local to DC, she is currently on residency at the Oregon College of Art and Craft, so we caught up online. Below is part I of our conversation… keep your eyes peeled for part II!

Anne Smith: Would you tell us a little bit about Tripps Run and your experience walking that path? What drew you to explore the stream?

Sarah McDermott: Tripps Run was actually kind of a random choice in that I wasn’t setting out to map a specific waterway. I was trying to follow any sort of urban waterway wherever it would lead me. With that said, I ended up being specifically drawn to Tripps Run by the surrounding neighborhood because it’s in an area that feels like it’s situated in this specific time period; it feels very late 60s, early 70s, maybe.

I just thought that was really interesting, so I was hanging around in that neighborhood a little bit, thinking it’s not developing in the same way that certain other parts of suburban DC are. And then I noticed Tripps Run running through it. And I had already had this waterways project in my head, so I thought, OK, let me mess around with this stream, see what’s going on with it.

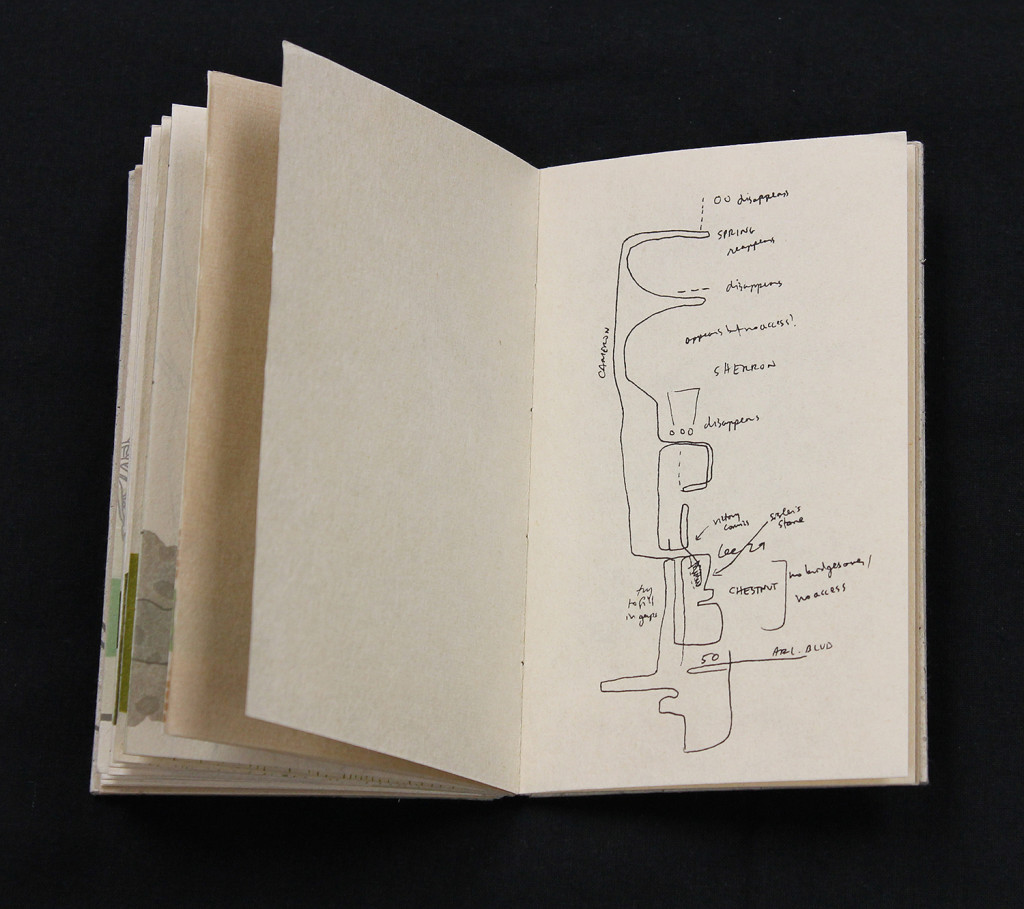

So, I ended up walking and driving the length of it because frequently, when I was walking I would get stopped by something, it would just disappear into an area that I couldn’t access. Either there were fences or bramble or people’s properties abutted in a certain way that I couldn’t access it. So I ended up, at a couple points, having to drive all over the place trying to figure out where the next point of access was.

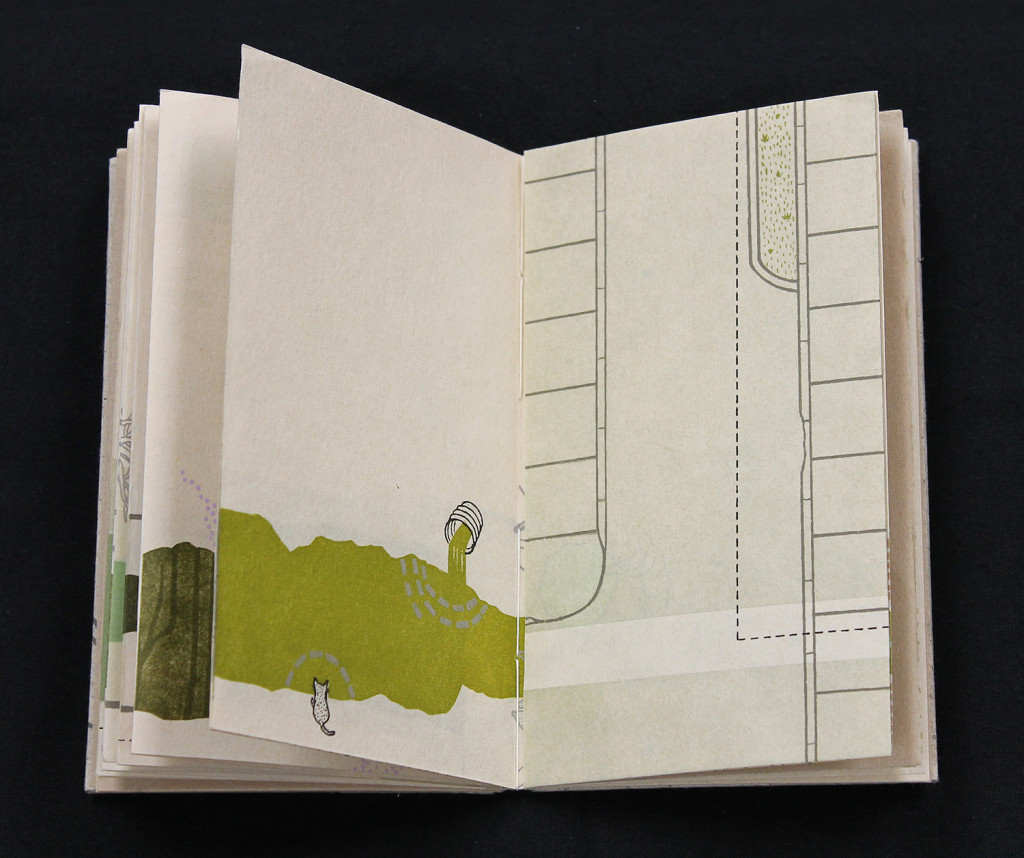

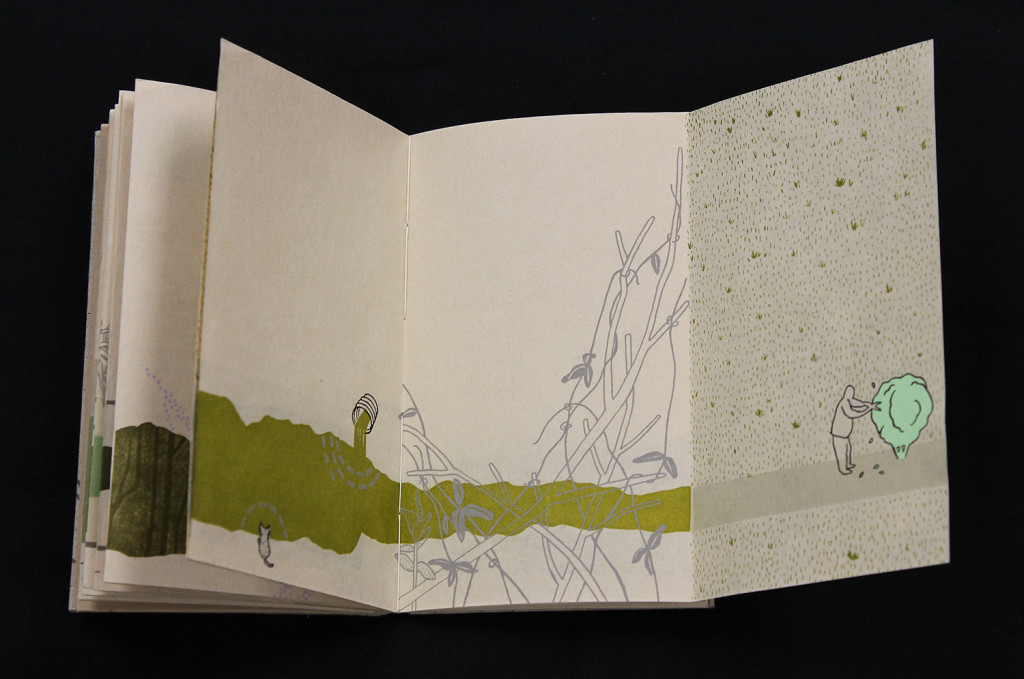

At the end of the book there is actually a little map I was drawing as I was doing that. And so it’s kind of loop-de-loop.

Hand-drawn map in Channel & Flow.

Hand-drawn map in Channel & Flow.

AS: So you had this interest in waterways but Tripps Run was also compelling because it was mysterious or kind of an oddity? Something that doesn’t get explored very often?

SM: It definitely had that feeling of being ignored or forgotten because everything was growing up around it. It’s kind of funny because we’re in a time period where people are really using waterways and capitalizing on them for ideas about nature, ideas about what a city should be: using the edges of a river as meeting places, as gathering places, walking and meandering along the river as a way of enjoying your city.

So, there’s a lot of movement to uncover waterways, and [the state of Tripps Run] struck me as the opposite. It was like, nobody cares about this. We’re just going about our business trying not to have it flood us out. And really, the only people using this stream in any way — because, that’s our relationship with water, is that we’re using it in some way or another — the only things using the stream were animals drinking out of it, which is sort of questionable because it’s not good quality water. There are ducks or cats drinking out of it and people have basically put their backs to it or ignored it.

That idea is interesting to me — obviously we are attracted to the idea of nature and what is natural and we want that, but only if it’s in certain ways.

So, walking along the stream ended up being a fragmented experience. To follow the whole stream, I’d have to walk directly down the middle of it. But even that wouldn’t work because it gets so piped and so basically I’d be crawling through tiny pipes and underneath yards, so there’s really no way to traverse the entire course of the stream.

And that was one of the things I wanted to explore: to what extent can I use a waterway to orient myself within a neighborhood that I didn’t know at all.

AS: I read the interview that you did with the Women’s Studio Workshop, and one part of it was called “Getting Lost with Sarah McDermott.” So I was wondering, what is your relationship to getting lost in the landscape? Is that something that you did often, as a kid, you liked to go explore, or if not as a kid, how does that play a part in your practice now?

SM: Yeah. Well, actually I continue to get lost. I mean, I never really get lost, but I definitely enjoy the feeling of not knowing exactly where I am, but knowing that, you know, I’ll make it out. Just because then you’re really actively engaged with your surroundings. The experience to me of going to a nature center and hiking trails that are completely delineated for you — that is not terribly appealing to me. Because while I’m interested in maps, following a map in that way kind of shuts you down to your experience of being present in the place.

So I like this feeling of wandering. There’s not worry because I know that I’m gonna get back, but it also gives you good thinking time and observational time. I often times will draw when I’m out and about.

I do think that I was given a good amount of leeway when I was growing up just to wander around. I’m impressed that my parents would do that, you know, because I was a kid in the 80s and 90s when it was like, everybody was worried about razor blades being in your Halloween candy and stuff. It seems like now, a lot of people keep their kids in the house and don’t let them run around too much. We were definitely given a lot of leeway in that respect, and so I think it really helped me develop my spatial awareness. And so I feel like I have a pretty good sense of direction internally.

AS: Since making the book, have you returned to Tripps Run?

SM: Yeah, but kind of the way in that everybody negotiates Tripps Run. I drive over it now, you know? I’ll be like, oh! There’s that stream I just made a project about!

I haven’t gotten into the stream, I haven’t continued my project, but I see it as part of the landscape. I’ll drive down Arlington Boulevard and go over it.

….stay tuned for Part II tomorrow!