Anne Smith: In my first encounter with The Sleep Series, I noticed how quiet and serene it feels. Then, as I spent more time with it, I began to understand all the frenetic activity implied by the piece: the way the baby’s brain is active and growing even in sleep, for instance. There is also all the activity of your making, as an artist and mother, with these brief windows of time (which could end at any moment) in which to work. How would you describe this piece? Do you see it balancing ideas of work and rest?

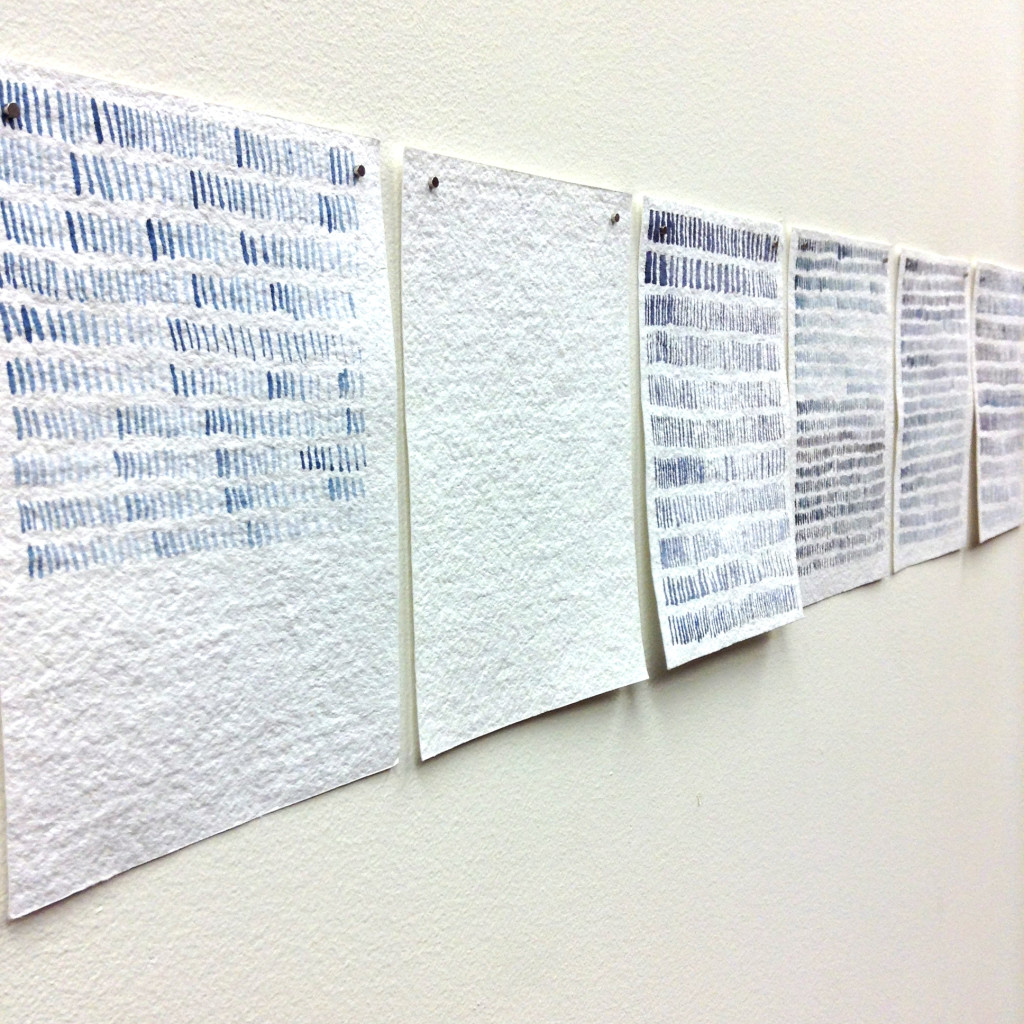

Sarah Irvin: I find it difficult to put a concise label on this work. In a basic sense, this piece is defined by limitations and in turn re-defines those very limits. Creating these paintings was a very direct response to having a one-month old baby and being the primary caregiver. I wanted to paint, but found it incredibly difficult to settle into a rhythm of working in very small increments of time that I had no control over. I chose to create work that was “done” when the available time was done, in this way the work was about the constraints and only exists because of those constraints. I worked this way for about two months and slowly transitioned into using the time to create different work without realizing it. Looking back it is multi-faceted. In one sense, I see the work as a visualization of my available time during those two months, in another I see it as a personal reconciliation to a new set of parameters as an artist and so on. I want to avoid the words “work” and “rest” when describing my time. I want to be well rested and I want to create rigorous work. The way my time is specifically broken up is becoming less relevant. I just move forward. The idea of leaving home to go to a place of work and returning home to a place of leisure is a fiction.

AS: What compelled you to measure your baby’s sleep in this way — with strokes of blue watercolor in rows, versus, say measuring with a timer and recording the time that way?

SI: I had watercolors at the ready because they are easy to set up and clean up. If your palette dries out, you can still use the paint later. This flexibility was what I needed. I used tick marks that were similar to marks in drawings I made while I was pregnant and not feeling well. I saw them as an indicator of the passage of time and like letters that form words in a very long, unreadable sentence. Recording every minute of sleep in a chart as hard data would have been obsessive, and I like to think that this is a more poetic record of early parenthood. Also, sleep is definitely a bluish, grayish, purplish, so color of the paint was an obvious choice.

AS: Where does the voice of a parent or mother fit into contemporary art today?

SI: If you look for it, you see that parenthood influences the work of many artists. This topic is as relevant as any other. However, first person accounts of parenthood as visual art are not typically acknowledged by major art institutions. It is important for artists to keep making work that engages critically with the experience of parenthood and for institutions to recognize and exhibit this work. If artists and curators take a chance and accept this as a valid topic, we will see what comes of it and no one has to figure out if, why, how and to what extent it is being ignored.

AS: What books have you read lately that have been part of your thinking around this project?

SI: The last three books I read were The Mother Knot by Jane Lazarre, Feeding the Family by Marjorie DeVault and Family Man by Scott Coltrane. Right now I am reading The Mermaid and The Minotaur by Dorothy Dinnerstein. I try to consume as much writing as I can about parenthood from as many angles as possible.

Note: The artist answered these questions while her daughter was sleeping.