Read the poetry from the exhibition here.

Crop Rotation, Douglas Luman (Click play to listen to the poem)

Douglas Luman & Alice Quatrochi

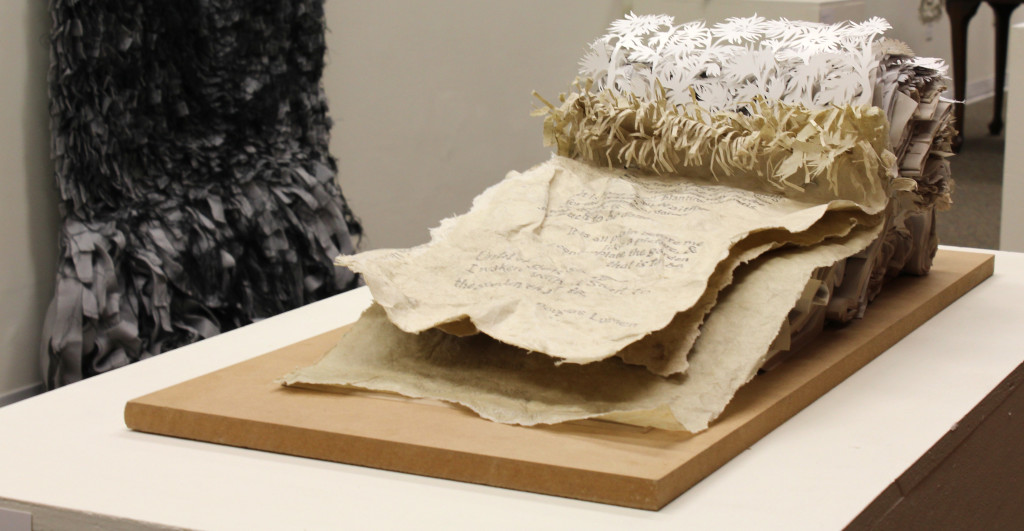

Fantasy sprouts Fallow

(Quatrochi, 2015)

Sculptural Book: Appropriated Paper and Handmade Flax

36” x 5” x 10”

Douglas Luman’s sourced statement serves as inspiration for this sculptural book. The pages wheel around to juxtapose a prolific fantasy followed by a consequential reality of neglect. Pages depicting this garden fantasy are constructed with investment brochures that serve to multiply delusions of ‘projected growth’. Their convoluted folds trace the aesthetic pleasures of inconsequential ruminations. The result of this prolonged indulgence is a manufactured desert depicted with handmade flax paper. The book’s cyclical form is supported with a wire armature.

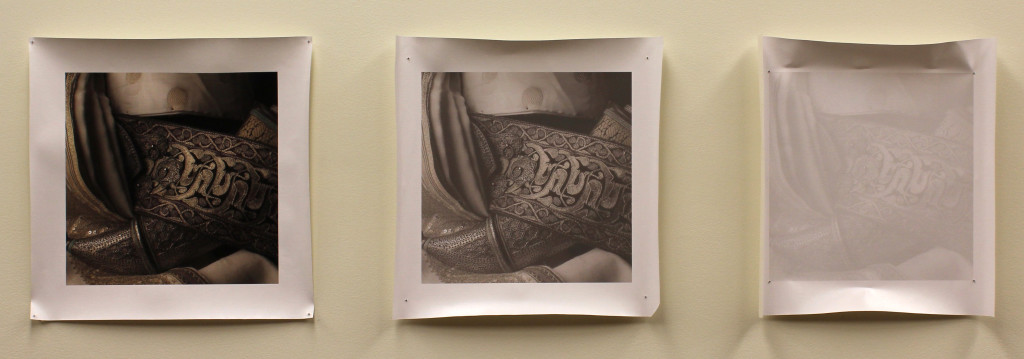

M. Mack & Noor Hamidaddin

Janbiyah (Hamidaddin, 2006)

35mm digital photograph

12” x 12” each

An investigation of familial lineage, considering both family of origin and family of choice, the poem aims to take a view tightened to ambiguity, as the combined textures in Hamidaddin’s photographs blur sign and signified. A dangerous object can become beautiful when viewed a certain way, or in certain limits. So, too, a memory.

Melissa Hill & Sarah Batcheller

Kismet Tapestry (Hill, 2015)

Felt, Thread

39” x 102”

The Kismet Tapestry found inspiration in Sarah’s work primarily due to its interrogation of identity. In much of my work I explore the uniqueness of the Self, juxtaposing it to that of the infinite Other. In the quest of self-discovery one actually seeks to uncover their own uniqueness. The Kismet Tapestry draws upon the notion of self-discovery. It acts as an attempt to visualize all of the nuanced threads and components that we construct and combine to formulate what we identify as the Self. In much the same way that Sarah’s future is impenetrable, so too is the bottom of the Kismet Tapestry unfurled – a story waiting to be written – a Self waiting to be constructed. The tapestry that is our past and the unwoven fibers that are our future come together to form that which is us. Indeed, our own uniqueness is something that, as Sarah states, is sculpted over time.

خرید vpn

Ah-reum Han & Mike Walton

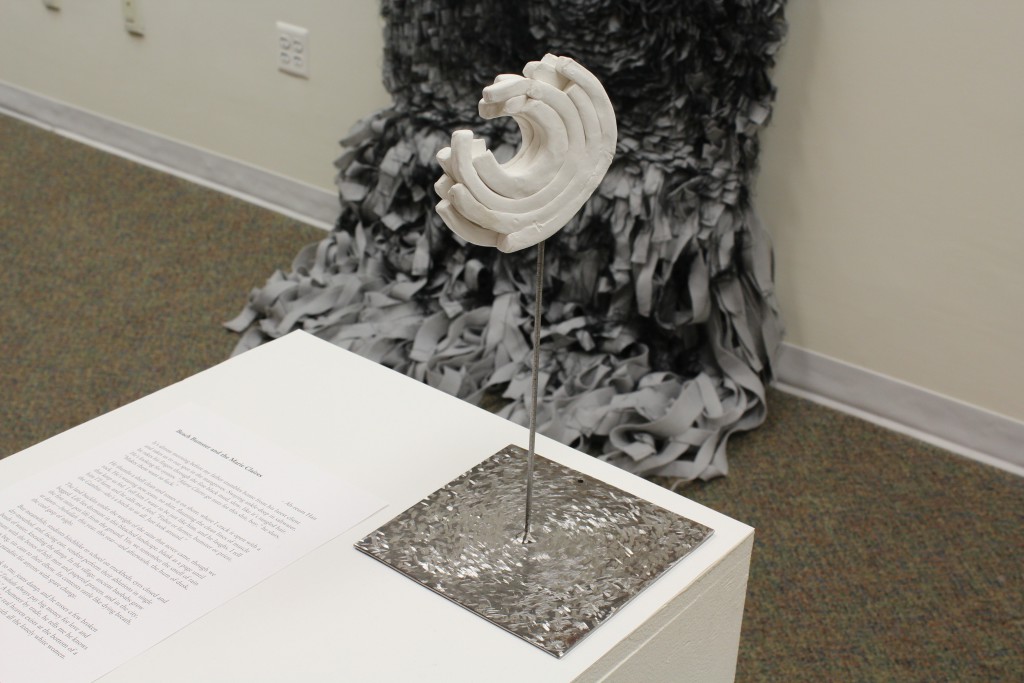

Harmony (Walton, 2015)

Cast Stone and Steel

8” x 8” x 13”

As contemporary artists we draw on the legacy of past artists. Their achievements provide the foundation for us to build upon and have the authority to challenge not only ourselves but our viewers. Our inheritance is the mandate of change. This is our lineage and we cherish it. This allows us as artist to raise difficult and troubling issues to the public forum, for awareness and for debate. Solutions are best derived by the minds of many, working together in concert. Perfection or utopia is not the goal. Harmony is the goal.

Marcos L. Martínez & Josh Whipkey

Untitled Sketches (Whipkey, 2015)

Pencil and Photo Transfer on Paper

7” x 7”

Martínez: What stories do we choose to pass on? How do we convey memories? If a memory is merely the mimeograph of a prior memory—a new imprint of the past, blurred yet fresh—then how do we honestly transcribe the past? For me, lineage is laden with gaps, stories told, retold, and (through the reinterpretation of memory) untold.

Whipkey: Art is my birthright. It is my heritage. It is the lens through which I see the world, and through which I see possibilities for a world that, at times, seems to have lost all semblance to the world I dreamed about as a child. To unearth that history is to place voltage on a line that has been forgotten, frayed, and torn—it is to awaken memories… angels and demons.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31GTIvDDk00

Qinglan Wang, Anne Smith, & Ariel Goldenthal

Nameless Place (Smith, 2015)

Paper and Acrylic Paint

16” x 16” x 16”

What is the lineage of a homeland? How does a homeland survive in a body? These are the questions circling through Wang’s piece, interweaving images of land, air, and water to define the familiar, the extent a body can understand homeloss, and the vestige of a disappearing homeland. Smith and Goldenthal developed a combined response to Wang’s work. Smith’s colorful house-like structure is covered in paper leaves, reminiscent of the Hawaiian kalo leaves referenced in Wang’s writing. The house is colorful and basic — not specific to a particular home, but more like the standard house-shape a child might draw. Goldenthal’s dance performance plays in a window at the front of the house. The first part of the performance plays with rhythm and sound to depict Wang’s description of bones in the body and the Hawaiian Islands. The second performance reflects the separation that occurs with homeloss and the struggle of reaching for something that is no longer there.

Nikki Brugnoli & Justin Lafreniere

Reckoning Space, Series of 2 (Brugnoli, 2015)

Digital Photographs

8″ x 8″ each

Brugnoli:

[Obliterate and Rebuild] These are the only ways of knowing an Other and Oneself.

I grew up in rural, post-industrial landscapes on the edges of Pittsburgh. In 2014, when the deepest roots of my life began to lift from the soil of this earth, I revisited the coke ovens and slate dumps in that depressed, yet pungent landscape, and I explored countless ways to examine and mine the nuances of those unremembered spaces.

As a youth, I don’t recall ever looking out to the contours of that landscape to find beauty though I often remember looking down. When space collapsed, I discovered a distressed canvas-like structure of fractured glass, stones, and coal, broken into one million scattered pieces that I collected and kept hidden, like precious treasures for much of my early childhood. I gathered them when I was alone, and delighted in my deep need for secrecy, solitude, and silence. Trespassing into abandoned and filthy cellars I scoured waste and decay, and embodied the familiar stench of mold and rot. Armed with long sticks and carving knives, I tore through summer foliage, creating lines for safe passage and imagined expedition. When I became conscious of being unsafe I left these familiar spaces behind as if my feet had never marked the ground; as if the scars on my knees had been left by some other surface; something purer, something softer, than a land stripped bare of kindness and memory.

This work that grows from the shape and reference of these sites intends to give form to the quiet, yet blaring mystery of youth and the uncertainty of the tumultuous present and undetermined future. It is a tremendous collision of possibilities and impossibilities. The blurry density of saturated darkness and the eruption of light embedded into the silky skin of Mylar speak to the opposites that exist in us all. These are the shapes of sorrow and of loss, and they are mine alone to hold and to let go of.

[Remain]

Anya Creightney & Ariel Rudolph Harwick

Grandmother (Harwick, 2015)

Laser cut cloth on wood table

30” x 43” x 60”

The poem “Los Angeles” was born out of a need to both understand and forgive my paternal grandmother, a woman once staunchly opposed to my parents’ inter-racial marriage. I wanted the piece to feel almost childlike—observant and quiet, attentive and careful. At the same time, I hoped to illustrate a feeling of inherent, almost congenital danger, so setting the poem in my grandparents’ house, a space filled with insidious mixed message, felt like a natural parallel. Ultimately, I wanted a poem that felt vertical and domestic—hence the orange tree, and a poem pregnant with the aura of love in all its idiosyncrasy.

Like Creightney’s poem, Grandmother creates an intimate domestic portrait that initially evokes tranquility, nostalgia, and empathy, but upon closer inspection reveals a darker truth. Dinner tables are a gathering place where families both love and estrange, cherish and alienate. And though a lace table runner serves as a connection between generations—an heirloom passed from grandmother to daughter to granddaughter—it also serves as a physical division, separating one side of the family from the other. Lace is innocent and commonplace — seemingly a fixture of every grandma’s house—making it a poignant and subversive medium for the last line of the poem.

Kelly Lorraine Hendrickson & Brittany Kerfoot

I Am Become Death (Hendrickson, 2015)

Steel, Paper, Resin

60″ x 60″

Kelly Hendrickson’s sculptural piece visualizes the concept of the “Hyperobject” as coined by eco-theorist Timothy Morton. Hyperobjects are viscous and consuming. They are comprised of many different pieces and transcend time and space. They are responsible for the end of our life-world as we know it. This is the end of our Lineage. We can no longer look at/reflect on our world with anything other than nostalgia.

Destroyer of Worlds (Kerfoot, 2015)

In response to Kelly’s installation, Brittany created a fictional piece that centers around two main ideas: time as a “Hyperobject,” and the role humans have played in the detriment of both our environment and our society. In this “new world” setting, humankind has destroyed Earth and any semblance of a harmonious society, and must now navigate through an existence devoid of time and linear memories. Together, these pieces ask audiences to ponder the meaning of our current “life-world” and how we may be contributing to the end of it.

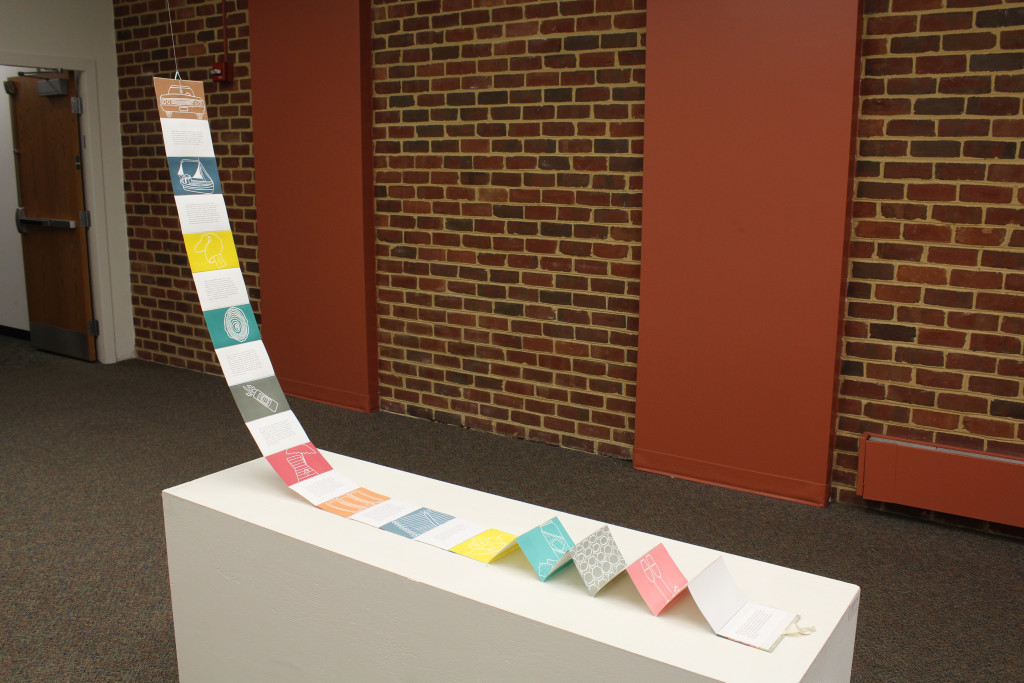

Melody Cook & Lina Patton

Shared Treasures (Cook, 2015)

Linocut

33” x 6” x 39”

Together, the text and images in Shared Treasures create a storybook that explores the small ways in which everyday objects link us to our families and legacies through ideas of memory, tradition, and the subconscious. The stories were gathered through interviewing a variety of participants, and each image was inspired from the details of that story. Ultimately, we hope the storybook reveals how the idea of lineage and the bounds we have to our families can be colored in even the smallest physical details and textures of our daily lives.

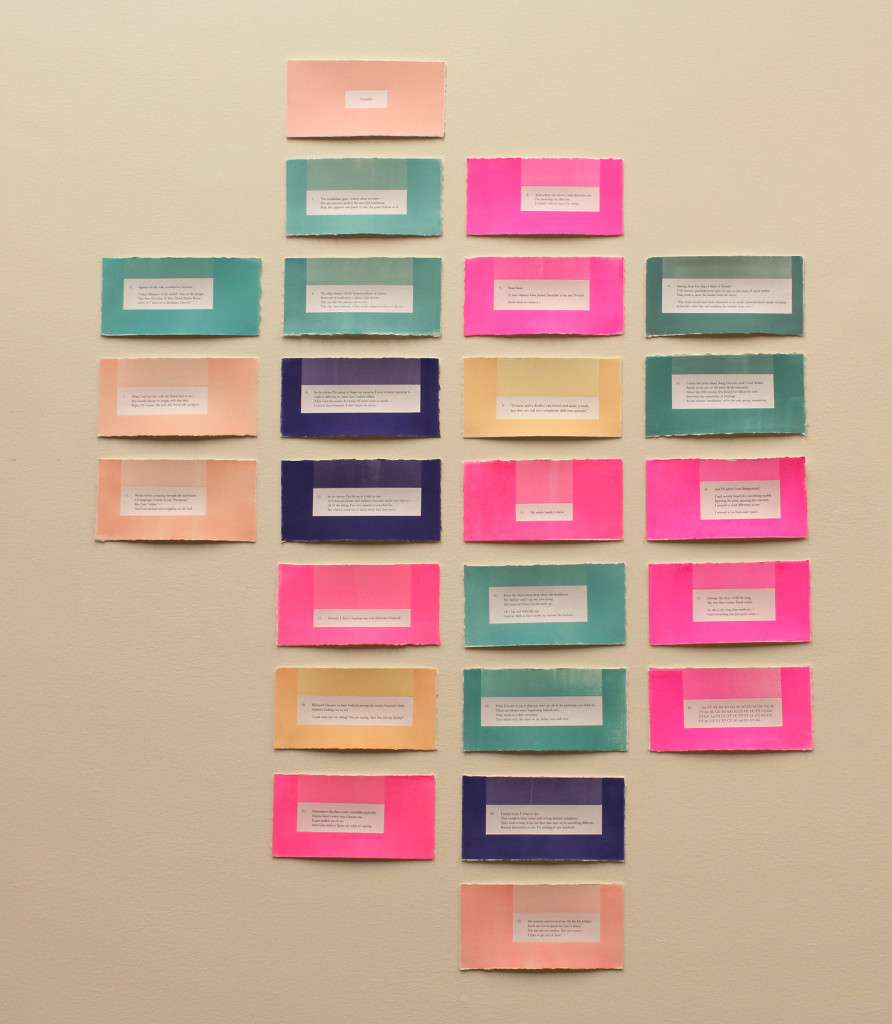

Marianne Epstein & Sean Pears

23andMe (Epstein, 2015)

Artist Book of Monoprints

7” x 3.5” x 1”

41” x 31” Display Size

The artists thought about the theme “Lineage” relatively linearly: what is the significance of our genetic line? How does it effect definitions of family? Of identity? Of race? These questions are rapidly evolving as genetic research and access to genetic records continue to proliferate, particularly in the form of consumer genetic testing. The words were inspired by Sean’s own foray into consumer genetics, as well as Dorothy Roberts’s cautionary treatise on the potential for genetic research to inscribe racial categories as biological, rather than political. The design was inspired by Marianne’s experience at NIH performing gel electrophoresis to isolate a gene, GRK3, implicated in bipolar disorder.

Two-Eyes, Benjamin Brezner (Click play to listen to the poem)

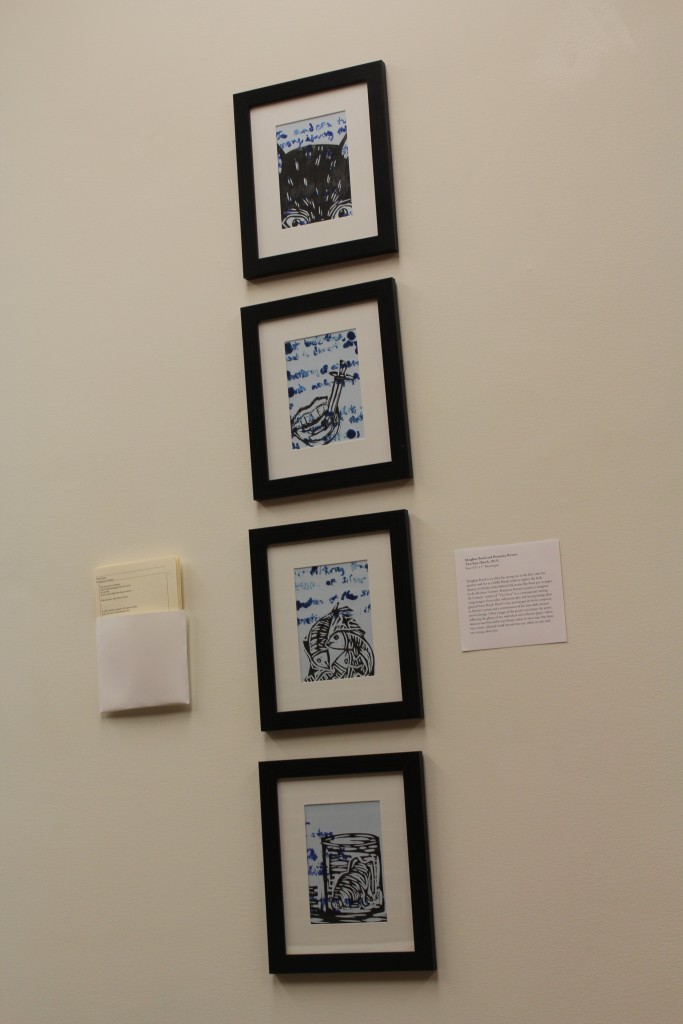

Meaghan Busch & Benjamin Brezner

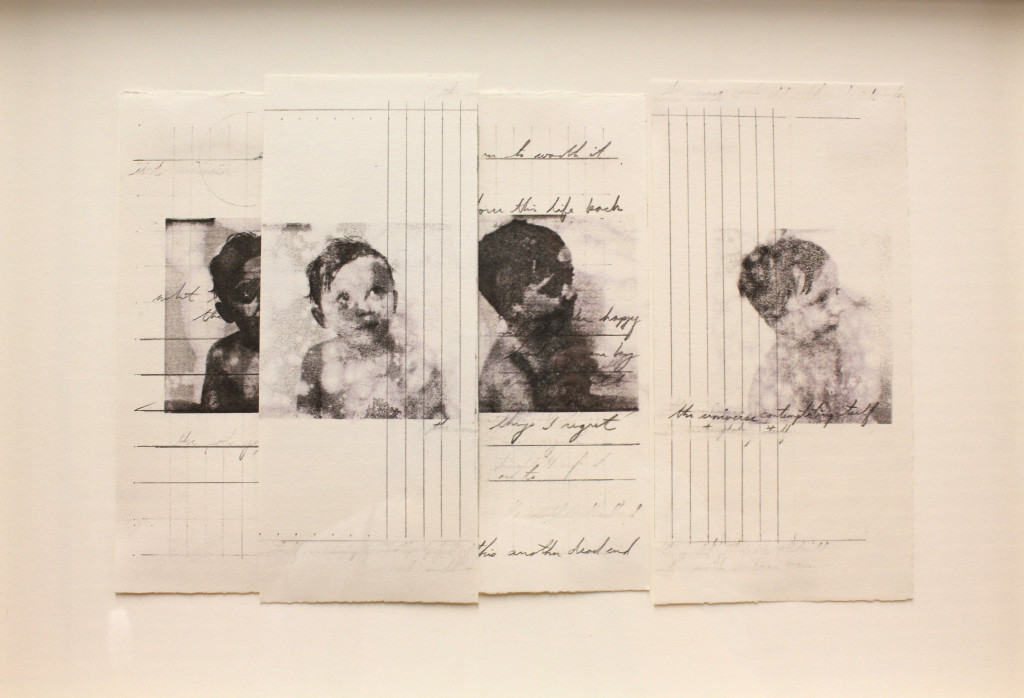

Two-Eyes, Series of 4 (Busch, 2015)

Monotypes

8.5” x 5” each

Meaghan Busch’s art often has strong ties to the fairy tales her parents read her as a child. Busch tends to explore the dark, dreamy world that hides behind folk stories like those put to paper by the Brothers’ Grimm. Benjamin Brezner’s poem re-imagines the Grimms’ version of “Two-Eyes” in a contemporary setting, using imagery from other influential tales and incorporating ideas gleaned from Busch. Busch’s four monotypes are both a response to Brezner’s poem and a continuation of her own dark, dreamy artistic lineage. Ghost images of the poem’s text haunt the prints, reflecting the ghosts of our individual and collective pasts—those times in our lives and in our history when we were sure that there was a secret, ethereal world beyond this one, when we saw with two young, clear eyes.

To Make A Shine for You, Holly Mason (Click play to listen to the poem)

Madeline Graham & Holly Mason

Cantate Domino (Graham, 2015)

Matte Print

8” x 10”

Religion and lineage are frequently intertwined, as religion is usually inherited through cultures and families—even when it is not embraced. Artistic expression, like lineage, is another commonality among religions: Nearly every religion features artistic expression, whether it be dancing, singing, painting, sculpting, writing, and so on. “Cantate Domino” captures one moment in which religion, lineage, and art intersect—an organist playing a 400-year-old Catholic hymn. The accompanied poem explores the notion of love as a religion and the beloved as a god; the concept of idolatry. The theme of music being married to practices of love and religion moves throughout.

Nathan Loda & Ben Bever

Traditions (Loda, 2015)

Oil on Panel

11″ x 12″

The traditions that link past to present has always inspired a sense of wonder and amazement in me. My painting is homage to an American artist, Andrew Wyeth, that painted scenes from his everyday landscape that capture the culture and sentiment that connect the American landscape and its peoples. The lineage of agriculture and specifically corn, is quintessential to American history going back to the earliest native peoples. Ben’s poem made me think about Wyeth’s painting “Seed Corn” and I wanted to create a painting the created a narrative about the influences and traditions we may inherit.

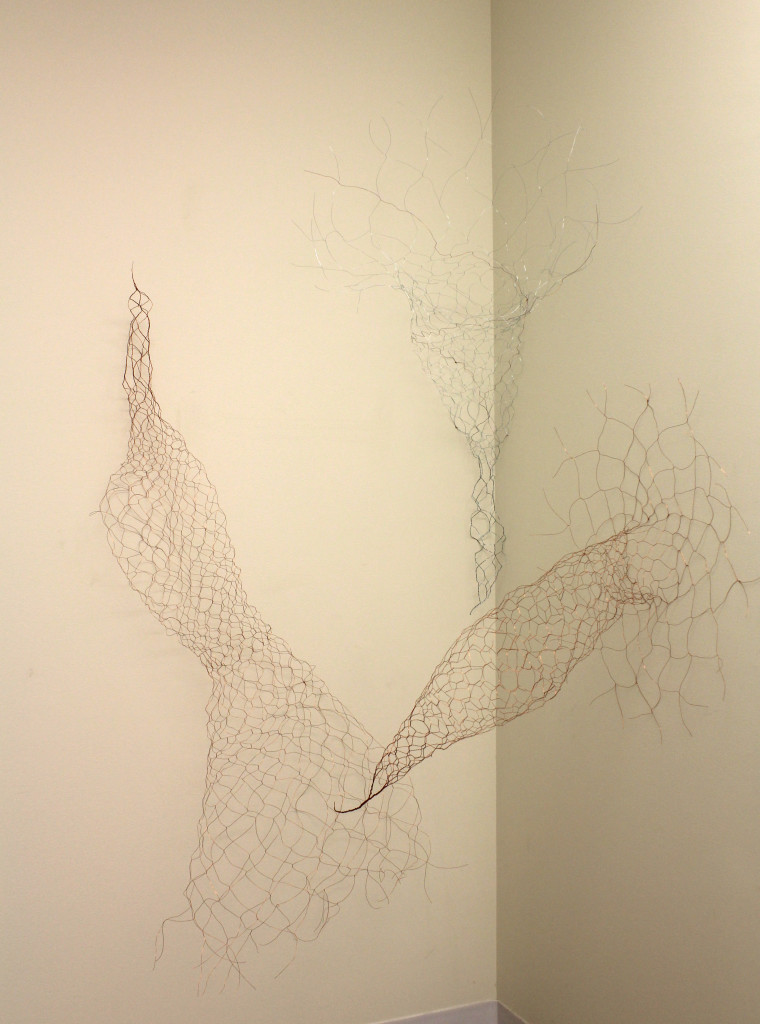

Sarah Zuckerman & Carina Yun

Seelen (Souls) (Zuckerman, 2015) and Xuètǒng (Lineage) (Yun, 2015)

Woven Wire Sculpture

Variable Dimensions

This work was created during my residency at GlogauAir as part of the MFABerlin Program through American University. I am interested in relationships, loss, and memory as they inform who I am. I am made of pieces of those who came before me, literally through DNA, but also in being raised by them. This idea is abstractly explored through these sculptural weavings of individual strands of copper and blue-colored wire.

Xuètǒng was created in response to viewing Zuckerman’s sculpture with particular focus on the strands of wires that appear to flow from one structure to the next. The poem explores the self in relationship to those that gave birth to us (mother and grandmother) and seeks to travel through different time periods in search for family history.

1 Comment

Add Yours[…] Call & Response 2015: Lineage […]