… part II of my interview with artist Sarah McDermott. See Part I here.

AS: Do you feel that, having experienced the stream, does that change the way you think about the area, or how you experience it when you drive through?

SM: Yeah, I mean for one because this project ended up being me mapping my experience of the stream, so it was kind of a personal, perception-based thing. But also, while I was getting to that point, I ended up exploring a bunch of other things, so I learned a lot about the history of the area.

Actually, right next to the stream, there’s this place called Tinner Hill that was the first rural chapter of the NAACP. So that was pretty fascinating. There’s actually a little, tiny historical marker there that you could just totally miss.

So, delving into it just gave me this increased sense of depth of the area, but that was kind of tangential to the project. And also, realizing the extent to which the stream had already been mapped — because when I did start to look there were FEMA flood plans, there are soil maps, you know because if it’s a certain soil quality, you need to build in a certain way. It’s all related to development. So you know, humans managing to live beside what used to be a very changeable, dynamic urban water system, but now they’re trying to constrain it so that people have an easier time dealing with it.

So I actually ended up talking to like fifteen different government agencies who all have different interactions with this stream. That was really interesting to me to be like, we have a really big government! It’s deep! There are government biologists, there are people related to sewerage, related to water quality, related to the flood stuff, related to development issues. Every component of that stream has already been inspected and mapped. I mean, I never had any ideas that this was a wild stream, but it was like, there is nothing that we don’t try to control about this stream or that we don’t try to understand or map. There is no element of it being wild.

AS: The data they’re collecting is of a certain nature that is measurable, but your map is more about that experience of being interrupted or fragmented — you know, there’s a history that their maps don’t capture.

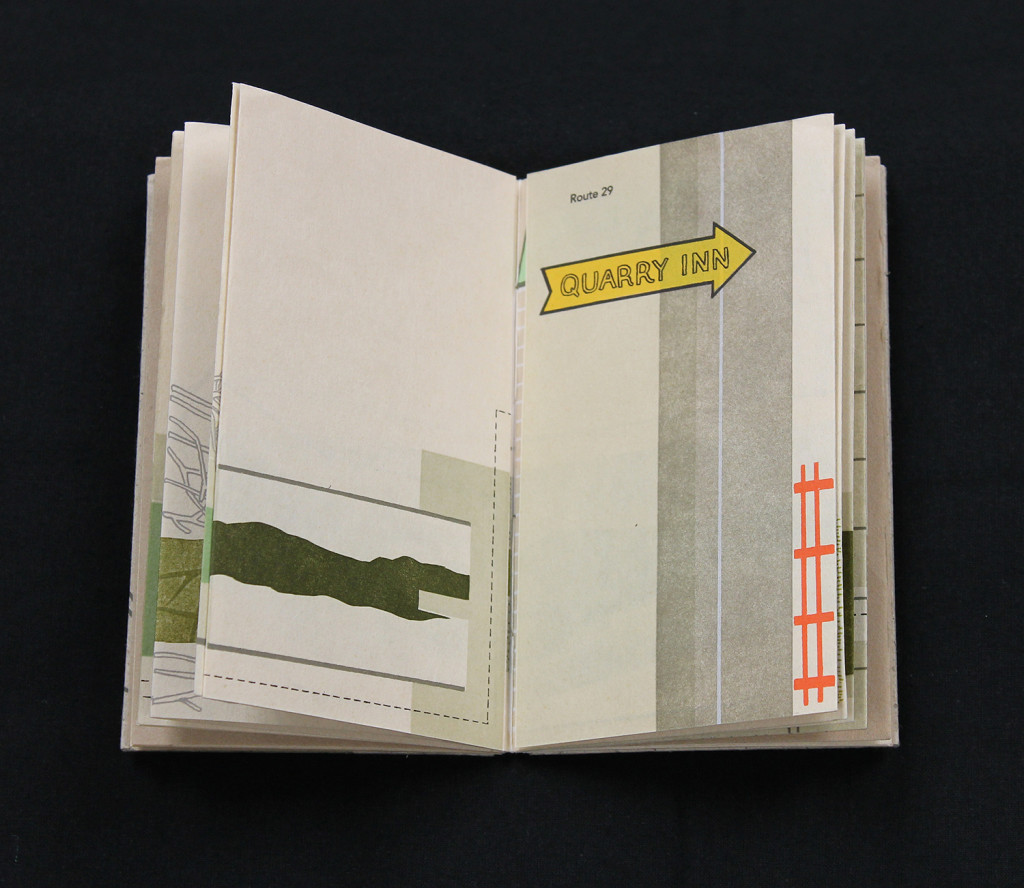

SM: Yeah, it kind of falls into a funny territory. I’ve had people ask me, “can I use your book as a guide book?” I mean, you can try but I definitely took artistic liberties. It’s that funny thing of, ok, I have this concept that’s constraining my project to give it form, but I’m also interested in making a beautiful object. So, this part?

This is two signs mushed into one. It’s one sign that had the Quarry Inn on it and then another sign that was an arrow. And I thought, well, I don’t really want to do both signs, but I want there to be a sign with an arrow in it and I wanted to do the Quarry Inn because I want it to be a clue to this section right here.

So, you know, I took liberties in terms of that kind of thing. So, it’s not really a map, it’s not really a guidebook, even.

AS: Yeah, that’s a thing I enjoyed about the work, like the other work that was in the Artists’ Maps show — it takes that kernel of an idea of a map as something that could orient, or not necessarily be geographically connected, but give the lay of the land metaphorically, even, about some network of data that’s collected by an artist. I enjoyed the way that people took liberties with that idea.

SM: There is a lot of work being made now that’s about data. I don’t know quite what to think about it because, you know, the maps that I was using, they’re supposed to give you knowledge for some sort of purpose. This is much more diffuse. It’s referencing knowledge and our desire to know, reflecting more on that desire rather than the actual knowledge.

So it’s interesting, all this data art is kind of reflecting on our desire to know, to contain, to understand, I think.

And then, also, graphically it can just be really fun. This constraint that you’re putting on yourself. That’s always the challenge when you’re doing any kind of project– what are the boundaries of this? What is the start and what is the end? Anything can turn into anything. It’s so hard to know, like if I’m doing research-based projects, it’s hard to know: where do I stop that research? Where is my little insertion point into this giant topic? Working on something like data or a map is really a very constrained way to look at a topic, so it’s liberating in a sense.

AS: One thing I think that ties together a lot of the work in the exhibit is that, like a traditional map, the artist has to filter the information, or say: this map is about this type of information. How did you decide what should go in and what shouldn’t?

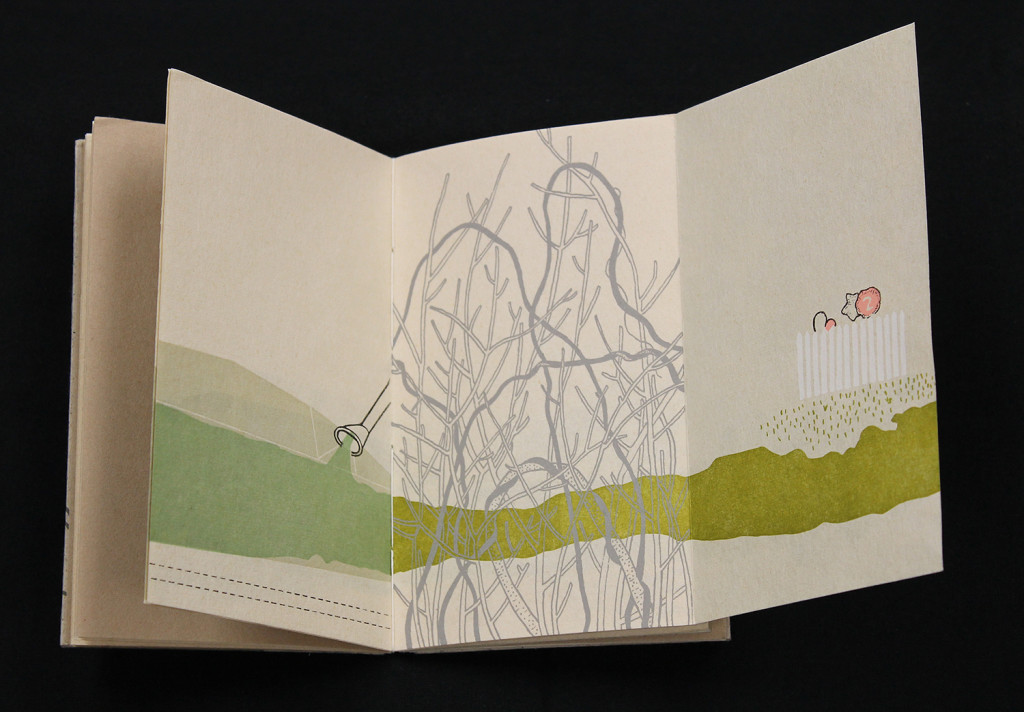

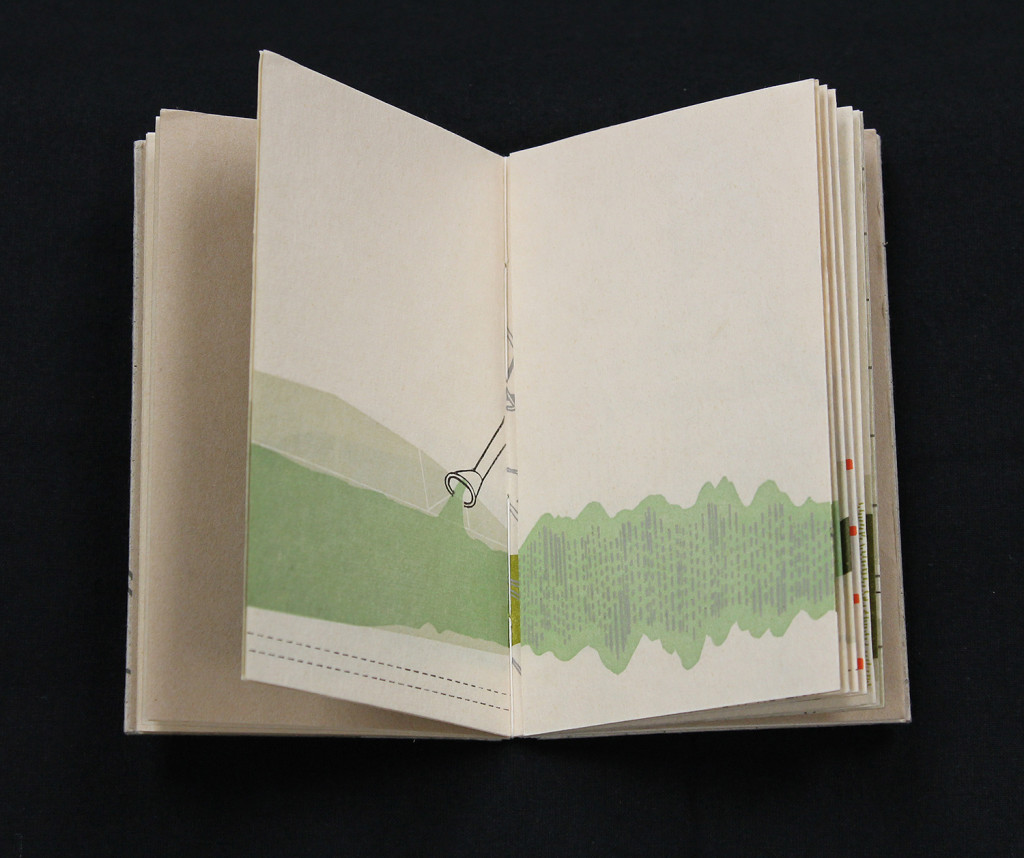

SM: Well, I basically decided based on which parts of the stream I could access. Every page of the book sort of functions as a vignette. [paging through the book] This is this section of the stream and this page is this section of the stream. It’s not like I took out a ruler and was gridding it out. It would be a different project. It was totally just how I thought it would function visually that made me decide that, ok, this width of a page represents this much of the stream. And it does something kind of funny because it equalizes every part. Because each page is the same width, it gives each part the same weight.

But sometimes I included, in between — like this section, where it goes underneath this building, this was the very next thing, but in between here and here, there was all this other stuff that maybe I couldn’t figure out how to represent graphically, or wasn’t as interested in. And I really liked the juxtaposition of certain things between these two. So it was definitely like a back and forth between what I actually saw in that moment and what kind of object I wanted to make.

I wasn’t following strict rules. And that’s probably an interesting project, like no matter what the outcome, it is what it is. It’d be less product-oriented; I just happen to be fixated on the book as an object. I want to make objects that I want to hold over and over again, because in some way, they’re beautiful, as opposed to being strict, “that’s what I saw, so that’s what’s there.”

1 Comment

Add Yours[…] https://fenwickgallery.gmu.edu/exhibitions/artist-interview-sarah-mcdermott-part-ii/ (accessed 31 August 2021) […]